Toward the end of the 1980s the new age traveller movement had been all but suppressed. The end of the decade saw a far more aggressive stance by the authorities, harsher trespass laws, and endless police roadblocks to sites such as Stonehenge. However, a new generation and music scene would proceed to take the countryside by storm….

The period of 1989-1992 saw an explosion of the rave scene in the UK, starting out with the Acid House scene, and later branching out into breakbeat, jungle and techno. A new generation replaced the hippies of 70s and punk generation of the 80s. In some cases, the punk generation of the 80s evolved into the raver/second generation traveller.

The opening of the 1990s saw more bad press for travellers with Michael Eavis banning travellers from Glastonbury festival. The 1990 festival saw an outbreak of violence in travellers’ field between the travellers and site security. A full-scale riot broke out and riot police were called in.

The event became famously known as ‘Battle of Yeo-man’s bridge’ and resulted in the cancellation of the festival the next year. Some account attribute the cause of the violence to heavy-handed festival security from Bristol. Eavis pointed to the travellers’ ‘’bitterness’’ as the cause of the trouble.

Either way, the beginning of the 1990s saw a surge in illegal parties and festivals that the nation had never seen before. Organisers worked through loophole in law by ensuring that the event went on all night. If events were parties that played music all night long, instead of festivals, it was difficult for authorities to break up illegal gatherings.

Where do I fall into all of this?

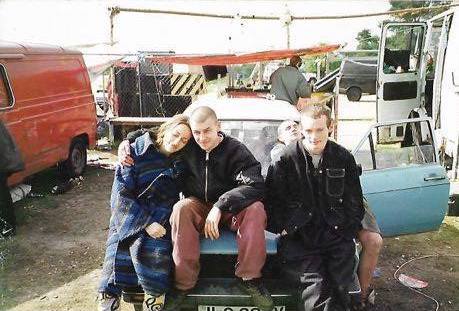

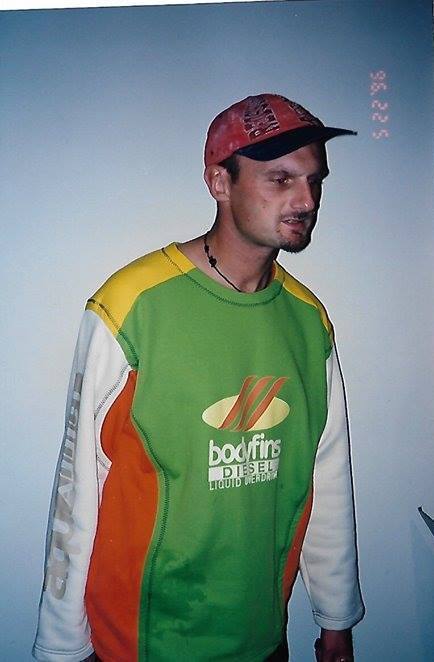

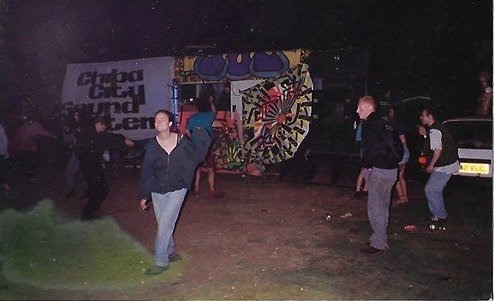

Below is a picture of my dad, in 1996, he was a part of this new rave generation. He became a part of the rave movement during the period of 1989-1995, travelling around with sound systems such as Spiral Tribe and the Liberators.

He has kindly provided much of the material for this week’s blog. I would like to thank him for scanning through his collection of photos, newspaper cuttings and Spiral Tribe memorabilia. Many of the details about the raves I will explore today are informed by accounts he has provided me.

It important to consider that transitions between different traveller generations were never rigid. When we consider generation waves of social movements and counterculture, we often consider them as often isolated from another, usually between a decade. Just as crossovers occurred between the hippie generation and punk generations during the Stonehenge period, there was a large crossover here.

According to my dad, the relationship between ravers and the older generation of travellers was a love/hate situation. The travellers liked the free parties, but didn’t want the ravers hanging around their sites. I presume some of this would be attributed to the large amount of police attention ravers received and the surrounding drug culture that got heavier as the years passed.

This was not a new narrative; the hippie generation and punk generation of travellers had also been at odds in their outlook. But eventually hybrids are formed, and in the eye of the outsider, they all begin to fall under the “traveller” label.

City and Country:

A migration between urban and rural spaces, as seen in the early 70s, returned in the 1990s. Road networks such as the M25 circuit around London became the hub for the search of free parties through re-direction points, flyers and word of mouth.

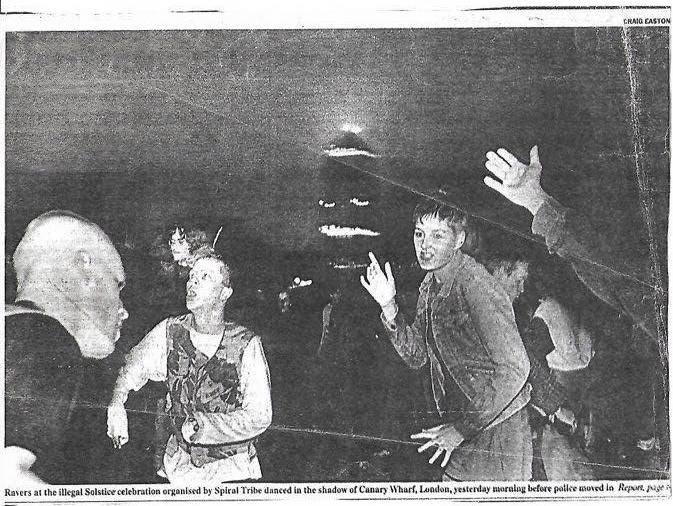

The impact of the police crackdown during the previous decade re-shaped the infrastructure. A negotiation between urban and rural spaces returned as we can see in the Newspaper cutting of ‘solstice rave’ in Canary Wharf, London 1992. The legacy of free festivals and Stonehenge and its spiritual iconography were passed on to the rave generation. Furthermore, this rave occurred after the infamous Castlemorton rave of the same year. A event heavily inspired by the Stonehenge free festivals.

The aftermath of Castlemorton could be attributed to the resurgence of pagan celebrations, e.g solstice, within urban spaces. It also shows the how the demographic of these free parties were predominantly city based.

Again,expeditions away from the city provide the same narrative of a desire for escapism and freedom. If you look at footage of Castlemorton and any other rave, it events look like a yearning toward to a more archaic time.

With names of sound systems such as Spiral Tribe, samples of tribal beats and people dancing in a trance like states, it clear the where the anti-modern sentiment lies. The use of large anthropomorphic totems built alongside sound systems added to this sense of ritual.

The free parties, alike to their free festival predecessor, held a ceremonial aesthetic in the gathering and people and music. The differences from tribes or free festival predecessors, was the monstrous rigs blaring out futuristic repetitive beats. The soundtrack of era certainly encapsulated tensions between finding euphoria in a rural oasis and a modern urban dystopia.

Again, the same issues with the local infrastructure began to arise again with disruption to farmland. At Castlemorton it was reported that 20 sheep were savaged by dogs over the course of the weekend. Tensions between the travellers at Stonehenge and Wiltshire farms were of the same cause the previous decade. However, according to other reports, the children of these farmers were also attendees at Castlemorton.

Issues of environmental damage were again raised. News reports and video footage convey the large amount of litter and lack of sanitation that caused long lasting environmental damage to sites.

1994 Criminal Justice Bill and aftermath:

The 1994 Criminal Justice bill built upon the 1986 Public Order Act and enforced stricter sections against trespassers and squatters. (A clause in the bill even outlined the issue of ‘repetitive beats’.) Some attribute Castlemorton as the cause of the bill after the large moral panic in its aftermath.

The bill had a large backlash from sound systems, football hooligans civil, liberties and animal rights groups alike. Numerous demonstrations against the bill in London were organised with turnouts of over 20,000 people. On the 3rd demonstration in October, Class War activists clashed with police inciting a full scale riot in the city.

During this period many sound systems began to move out of the country to organise free raves in Europe. This could be attributed to both the growing popularity of UK rave culture crossing over in Europe, and large amounts of negative police attention upon sound systems after Castlemorton and the 1994 bill.

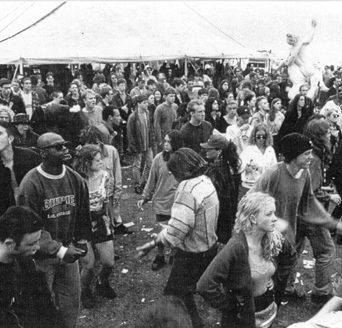

The photos below were taken by my father at the 1994 Milau France Teknival when he travelled with Spiral Tribe. The Teknival was organised up in the French mountains with no running water on site, thunder in the skies, and nearby picturesque rivers for swimming and bathing. Ironically, despite effort to branch away from the UK scene in light of the new bill; the French authorities were as equally brutal with their crackdowns. Military police were dispatched up into the mountains to shut down the festival.

Eyewitness accounts report of a brutal attempt at a roundup, with festival goers being dragged out of tents. The French authorities, however, were unable to contain the sheer number of people (4,000-5,000) and made a hasty retreat.

1995

The implementation of the Criminal Justice Bill provided greater opportunity for the police to violently crackdown on the organisation of illegal parties. Furthermore, police now had the authority to confiscate sound systems and provide hefty fines.

The Woodbridge rave in 1995 saw the impact of the bill with police roadblocks around the site to prevent the free party. My party reported to me that he travelled down in a van with decks and equipment for the party and was forced the ram through the blockade. The rave was on the anniversary of D day and lasted 2-3 days long nearby an air base. Eventually police entered in full riot gear. Arrests were made and all equipment was confiscated. The rigs/sound systems took months to be returned, showing the disruption the illegal rave circuit at the hands of the new bill.

Conclusions:

The end of the 1990s saw a fizzling out of illegal parties with the rise of commercial clubland, and new laws ensuring the cons outweighed the pros. The illegal scene and New Age Traveller are still alive today in remnants, but the large phenomenon it once was died out at the end of the 20th century.

Who knows, with an impending economic recessions, a number more of years of austerity, maybe both movements have the fruition to come to life once again…

References/Sources:

The Battle Of The Beanfield ,ed. by Andy Worthington , 2 edn (Eyemouth: Enabler ,2005).

James Hall, ‘When Glastonbury caught fire: The story of Battle of Yeoman’s bridge ‘, Telegraph , 20 June 2019