Last time we ended off with the emergence of the clear network of free festival circuits for new age travellers. This golden period incited a greater recognition from the public and press (for better or worse), and a peak number of attendances to free festivals.

In the previous article, I discussed the development of Stonehenge free festival and the people behind it. This time I will detail the developments during the late 70s and mid 80s. I will explore archived footage and images to provide in attempt to provide the most effective historical representation as I can.

Unlike the last article, it will be easier to give the reader a better footing due the sheer amount of raw footage and documentaries on Stonehenge festival circa 1979 onward.

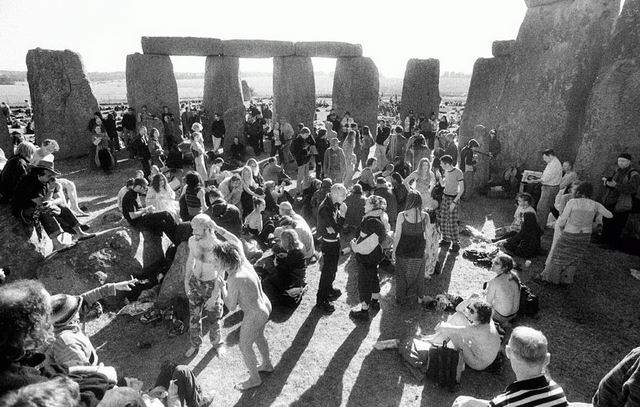

The most fascinating footage I found was recording of people walking through different sectors of the festival. The structure of Stonehenge festivals looks like a prototype for the contemporary open field festivals we see today.

This period of the free festival scene marked the introduction of a new wave of travellers. The anarcho-punk generation of the late 1970s slowly began to assimilate with the wider new age traveller scene. It was here that the free festival circuit began crossover with the wider political protests during this period of socio-political turbulence circa 1979-1984.

Furthermore, the growing number of economic refugees in Thatcherite Britain not only bolstered the size of the festival circuit and traveller community, but also revealed an emerging dark underbelly…

The new age explosion in context:

The impact of Thatcherism of the late 1970s certainly bolstered the numbers of the New Age Traveller movement. The economic recession during this period, and policies under the newly elected Conservative government, left many homeless. The only option for many was live out of their cars or vans and travel the roads.

Again, we can see from this period a second wave of diaspora from urban to rural. Unlike those who volunteered to drop out of society in the earlier periods, many of the newer travellers had little agency. I would consider this a major factor that bulked up the attendance of Stonehenge free festival to the likes of 100,000 people.

Also, within this period of depression, I think a lot of people used the Stonehenge free festival as an escape from their everyday realities. Their newly acquired lifestyle was hearkening back to more archaic times, away from the restrictions of modern life. What better place to channel this desire for the past and pursuit of freedom than the Druid site of Stonehenge?

As well as this, the independent community at Stonehenge provided people who were unemployed greater work opportunities and quality of life. People could use their skills and trades within the large co-dependent society.

It was in this transitional period that concreted the presence of the New Age Travellers within the rural countryside. The change to nomadically living in vehicles (some even tipis), and migrating to various camp sites around the country, broke down the old seasonal migration model of city and countryside.

If you look at the images and footage I have featured, you will see the large site of the free festival looks like something reminiscent of a Mad Max film. It is surreal in an age where most gatherings are highly government regulated and professionally organised, to see such a large independent self-sufficient society based within a free festival. You get a sense of pure freedom of those living on the Stonehenge site.

Origins of the convoy: mapping free festivals and political protests:

The iconic peace convoy that has become widely associated with the New Age Traveller movement did emerge until 1981. Travellers moved to the Greenham women’s peace camp to support in their protests against nuclear weapon sites in Berkshire.

Here we see a growing relationship between political factions engaged in protests against governmental policy, and individuals pursuing a counter-cultural, spiritual and musical lifestyle.

Returning to this ‘peace convoy’, a group 120 vehicles they moved away from the Wiltshire site in support of the Greenham protests. 1982 saw an even larger convoy of 135 vehicles set of for Greenham.

It could be argued this this increasing mobilisation between new age travellers and political groups is what ensued the government to clamp down on them so aggressively. The growing number of discontent people in protest was a threat to the government in the city, let alone in the countryside as well.

The Peak and its repercussions…

The 1983 Stonehenge saw a peak in attendance with eyewitness reports of approximately 30,000 people attending, and 70,000 visitors over the duration of the festival.

From the footage of Babylon Straight archived on YouTube you can see how amazing the innovation people employed during the festival’s peak. The highlight for me is a solar powered cinema showing blockbusters such as E.T. (If it worked anyway, looking at the grey English weather, i’m sure a diesel engine had to step in.)

The demographic of the festival in the footage also reveals a motley crew of hippies with shoulder length hair and eastern woven patterns, bikers, punks, rockabillies and dodgy mullets galore.

It was in this period that things began to become problematic. Tensions with the National Trust begun with attendees on site cutting down trees for wood. National Trust was forced to intervene and provide a surplus of wood to prevent further damage the heritage site.

The overpopulation of the festival became a paradox to its surrounding spiritual and green ideologies with destruction of protected land. Perhaps the site can be considered a microcosm for how overpopulation places strains on infrastructure and drains environment resources, even for those who aim to preserve it?

Alongside this issue, the heroin epidemic of the 1980s had also began to seep into the new age traveller scene. The National Trust demanded that any heroin dealers were to be removed from the Wiltshire site by festival organisers.

In response, any of those who were caught using or dealing heroin were evicted from the site. This system of self-policing for trouble makers became a system for all free-festivals and later free raves in the 1990s.

But these two factors highlight the impact of the city diaspora upon the sacred national trust site. Firstly, the transfer of the social issues within the city via economic refugees into the site of Stonehenge. Secondly, the repercussions of over-population on the festival site’s infrastructure, its position as an alternative state, and its surrounding natural features.

1984: The Turning point

It was looking to be the beginning of the end in 1984. The year the last free festival was held at Stonehenge. The police tactics in dealing with traveller groups became far more draconian.

By 1984, with the rising tensions and diminishing tolerance; Police, National Trust, English heritage and local land owners proposed a plan to block access to the Stonehenge site the proceeding year.

It was during this period in time that authorities began to respond with violence not seen since the 1974 Windsor Free Festival.

Beyond fall outs with the authorities, tensions between political activists and travellers had also started to occur. In 1984, Travellers disrupted a peaceful animal rights protest by pulling down fences.

Travellers then moved down to the US air force base Boscombe Down, again using the fence tearing tactic. The consequences was the destruction of the months of negotiation for a fragile relationship between peace activists and USAF airbase security. Some accounts state that the police in the aftermath responded aggressively with riot vans that cut up convoys and smashed windows of vehicles.

After the Porton Down licensed festival, a morning raid was conducted by riot police who had been suppressing nearby miner strikes. The aftermath was 360 arrests, imprisonment for a fortnight without charge, and hefty court charges.

The last Stonehenge festival had a turnout of approximately 70,000 people. This festival is where I found the largest amount of written accounts on the web. I will provide links to them at the end of the article.

Eyewitness accounts shade light on druids performing rituals at the stones, naked revellers running about the place, strange crossovers between Punks and Hippies in the crowd, burnt out heroin dealer’s cars; all to the soundtrack of Hawkwind…

The downfall of 1985

1985 opened with the eviction of the Rainbow Camp in Molesworth, Cambridgeshire in February. Peace protesters, travellers and members of Green organisations were evicted by the largest recorded peacetime mobilisation of troops.

The convoy was left to wonder after this, with various injunctions, media smear campaigns and police attention all closing in on them.

The event that put the final nail in the coffin for Stonehenge free festival, and the traveller/free festival network, was of course, The Battle of Beanfield. I won’t delve too deeply into the event because Andy Worthington already has a fantastic book providing many different accounts of the event. You can also find many other documentaries across the web.

1985 saw an optimism of the festival going ahead despite various injunctions from the National Trust. A convoy of 600 travellers however, were met with a force of 1,200 police officers. Dubbed ”Thatcher’s Army”, the core of police officers had recently quelled the Miners Strike the previous year. It was only a matter of time until the new age travellers fell into their cross-hairs.

What proceeded has been reported as some of the unprecedented brutality at the hands of the police force. Men, women and children were beaten to a pulp, convoy windows were smashed and vehicles were burnt out. Out of the carnage 16 travellers and police men were hospitalised and 500 travellers detained.

The convoy was broken, many travellers left the Beanfield with neither their homes or belongings. The 1986 Public Order Act gave police greater powers to evict trespassers, ensuring that any future attempts to re-establish free festival sites were quickly locked down.

The Mid to late 1980s was a pessimistic time for New Age Traveller. After Beanfield, the movement was splintered with little hope of regrouping to its previous numbers. But a growing scene of strobe lights, repetitive beats and doves would change that all. More next time…

References and sources:

The Battle Of The Beanfield ,ed. by Andy Worthington , 2 edn (Eyemouth: Enabler ,2005).

Barbara Bender, Stonehenge:Making Space (Oxford:Berg,1998).

Alan Lodge , One Eye On The Road: A Festivals & Traveller’s History () <http://digitaljournalist.eu/OnTheRoad/>

Jack Mckay, Stonehenge Free Festival 1984, diary (2012) <https://georgemckay.org/festivals/stonehenge-84-diary/>

Frankie Mullin, The Beginning of the End for Britain’s Illegal Raves: Remembering the ‘Battle of the Beanfield’ (2015) <https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/avyg4p/battle-of-the-beanfield-30-year-anniversary-344>

Paul Sorene, ‘Sex n Drugs n Rock n Roll’ – The Last Stonehenge Free Festival in Photos (1984) (2019) <https://flashbak.com/the-last-stonehenge-free-festival-in-photos-1984-417008/>