By the 1970s the free festival scene had begun to take full flight with several festivals organised in Windsor, Isle of Wight, Stonehenge and Glastonbury. The most recognisable festival to come out of this period is of course, Glastonbury. Glastonbury has not only become a staple in rural festival culture, but in wider British culture. In 2019 it became the largest greenfield event in the world.

All images/artefacts used in this article are courtesy of The Museum of English Rural Life. If you interested, you can view them at the museum on University of Reading’s London Road Campus.

These Wellies signify the entrenchment of festival and counterculture into rural life and infrastructure. Why you may ask? These Wellington boots belong to Glastonbury Festival founder, Michael Eavis. Before his creation of the festival, Eavis was a dairy farmer at his farm in Pilton, Summerset (he remains a farmer outside festival season). He was inspired to start the festival after seeing Lead Zeppelin at an open-air concert.

This alongside Michael and Jean Eavis’ admiration of ‘’flower power’’, persuaded him to organize the first festival in 1970. Jean Eavis is often overlooked in the establishment of Glastonbury festival. Jean was Co-founder of the festival and helped in its running until her passing in 1999. People often place Michael as the face of the festival, but it was the both of them together that helped build Glastonbury to what is is today.

The debut festival was £1 entry with T-Rex as headliner. The attendance of the festival was small with only a few hundred hippies/travellers. The only archived footage of the event I could find is available on an ITV interview.

The proceeding festival in 1971 transitioned the event into a free festival (with the help of sponsors). ‘’Glastonbury Carnival’’ saw the debut of the iconic pyramid stage, with headliners such as Hawkwind and David Bowie. The weekend saw an attendance of 12,000 people and a television recording.

After the 1971 festival, Glastonbury had an 8-year hiatus. It was in this returning period that saw the festival’s rise to a commercial success, attracting attendees from all over the world.

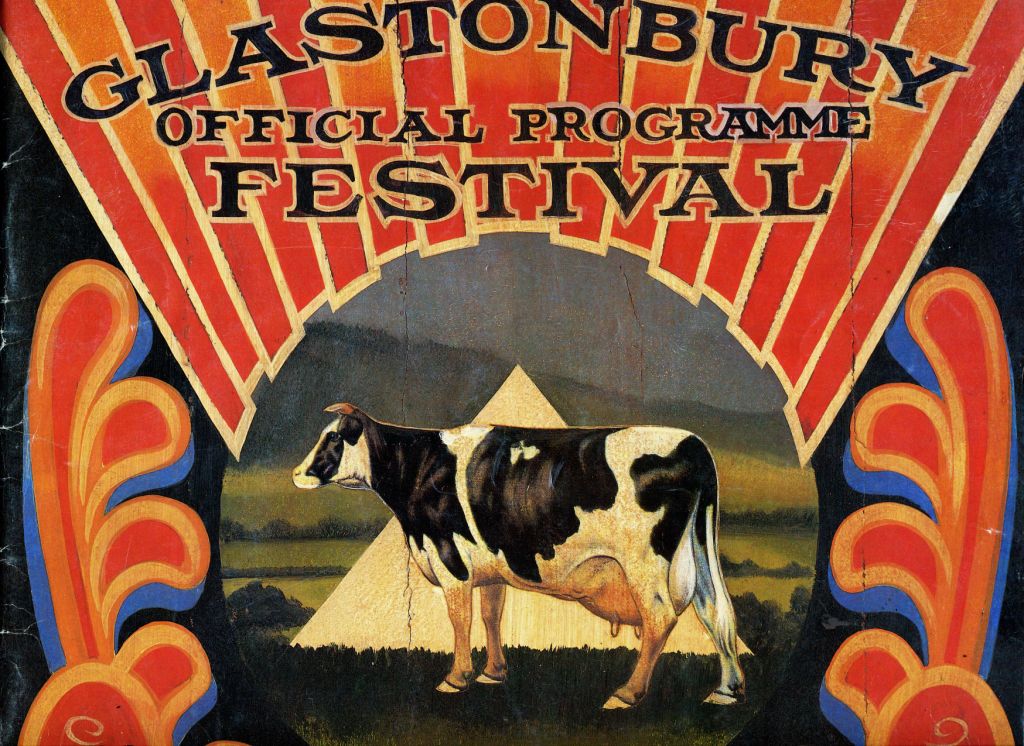

The iconography of this 1989 poster mingles together Eavis’ identity as dairy farmer and festival organiser by merging the cow and pyramid stage into one symbol.

It is significant that Eavis’ inspiration to start the festival was rooted in his boredom of being a dairy farmer. Maybe a loss of traditional rural culture, such as folk culture, could be attributed to this?

Either way, his move to create the festival was a big step in mingling the rural countryside alongside urban counterculture. It could be considered his attempt to modernise the English countryside with popular culture.

Despite the potential abandonment of traditional rural culture, Glastonbury holds heritage as a site of spirituality prior to the festival. Glastonbury is often considered the ‘isle of Avalon’ and Druidic centre of learning.

Again, we can see this mingling of music counterculture and mysticism. The festival today still facilitates such practises with ‘The Healing Field’ and ‘The Sacred Space’ sites to practise ritual experimentation.

Alternative practises previously conducted in the city, with spaces such as Gandalf’s Garden, were now facilitated within the rural through music festivals. In this sense, the Glastonbury festival re-vitalised the space’s heritage as a Drudic site by placing it alongside music culture.

Beyond Glastonbury, the other spiritual site that facilitated both mysticism and music festivals was Stonehenge. But as we shall see in my next blog, the repercussions to these practises were far less hospitable.

Beyond this mingling with popular music culture, Eavis also allowed a group of travellers to settle on the Glastonbury site during the festival. This commonly became to be known as the ‘’traveller’s field’’ on the out skirts on the festival site. Unlike other rural landowners’ relationships with traveller groups, this was one of the few that remained harmonious (for a time anyway). We will get to that later…

References and sources:

Beyond New Age: Exploring Alternative Spirituality , ed. by Steven Sutcliffe, Marion Bowman , 2 edn (Edinburgh: ,Edinburgh University Press, 2000).

The Battle of The Beanfield, ed. by Andy Worthington, 2 edn. (Eyemouth: Enabler, 2005)

James Deblingpole, ‘A Good Man in Glastonbury ‘,The Independent ,18 June 1995

Judge Rogers, ’12 moments that made the modern music festival’, The Observer, 29 March 2015

Michael Eavis looks back on 50 years of Glastonbury: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lgoSt-chrm0